Jumping in Atom

Right now, Atom can execute a simple procedure like adding and subtracting a few

numbers. However, it doesn’t have the ability to make decisions of any kind. The

solution to this problem is to add two things: a register comparison operation,

and conditional jump operations. After comparing values, the jump operations can

skip over or repeat code. These are the basis of things like if and

while or for loops.

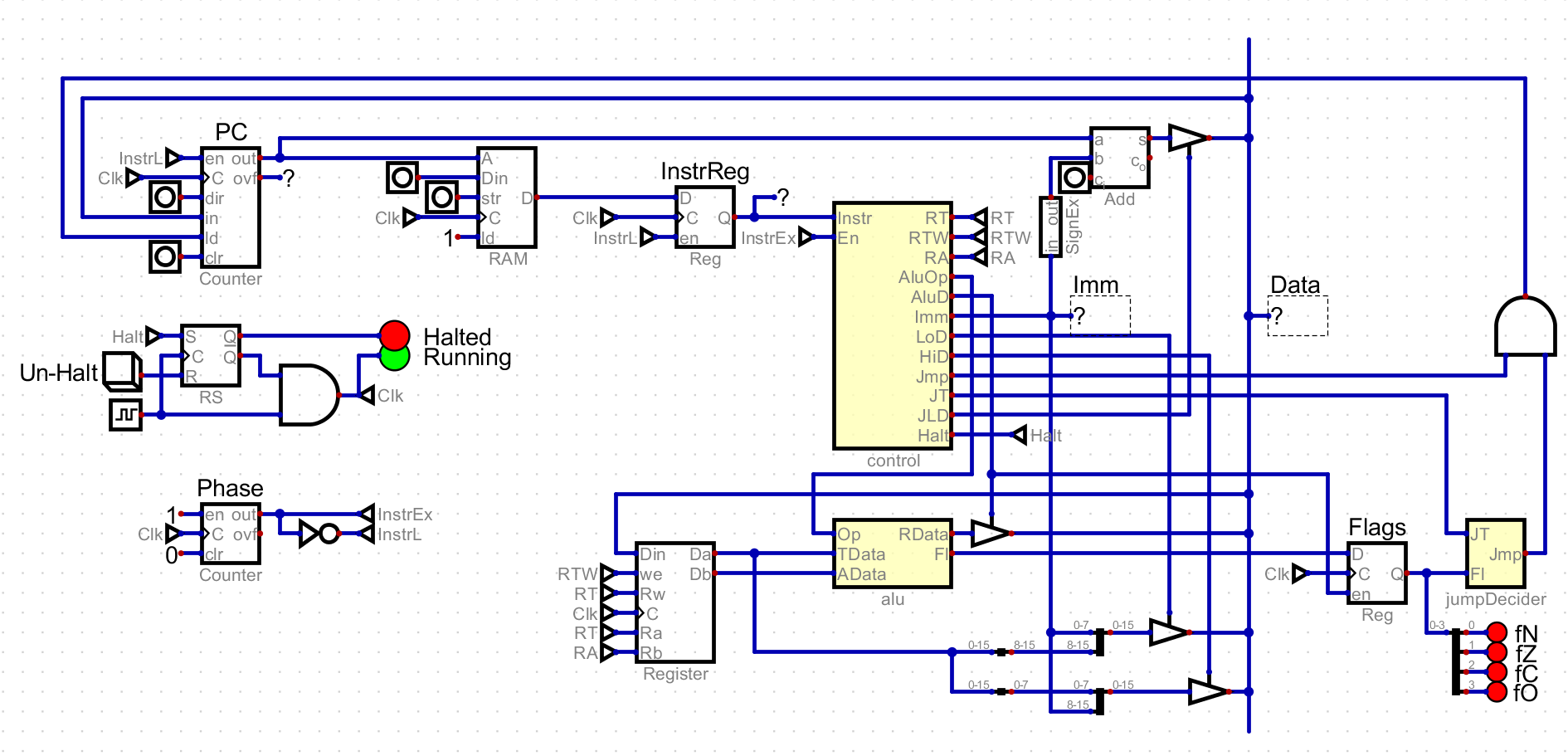

Once I have implemented these instructions, I will be able to write a program that calculates the first Fibonacci number that is under a given value. This page covers changes between #register-atom and jump-atom in the git repository.

Types of Comparison

There are six comparisons that I want to be able to execute: equal, not equal, less Than, less than or equal, greater than, and greater than or equal. Some of these comparisons will require that I make a distinction between signed and unsigned numbers, which has not been needed up to this point.

Two of these operations, equal and not equal, don’t depend on if the data is signed or unsigned. This is because, regardless of that fact, if you subtract to equal numbers you get zero, and if they are not equal you get something other than zero. This means that simply checking if the result of the operation is zero is sufficient to check for both equality and inequality.

The remaining four operations differ depending on if you are operating on signed or unsigned data.

Ordering Comparisons

I will refer to the remaining four comparisons as ordering comparisons as they

establish and ordering of values. In order to evaluate these comparisons, I only

need to define one more thing: how to determine if one value is less than

another. Once that is defined, the other three can be defined using it and

equality which I can already do. The equations for the remaining three are

listed below, where E is equality and L is less than.

| Comparison | Equation |

|---|---|

| less than or equal | `L |

| greater than | ~L & ~E |

| greater than or equal | ~L |

This means that I only need to define the less than comparison for both signed and unsigned values.

Unsigned Less Than

For unsigned numbers, determining if the target is less than the argument is simple. When subtraction occurs, if overflow happens then the argument must have been larger than the target, and so the target is less than the argument. That is it, just use the value of the carry from the subtraction.

Note that it is not sufficient to check if the resulting signed value is

negative. For instance, if you had a large number like 0xFFFF and

subtract zero, you will end up with a result that looks like a negative signed

value, even though clearly the maximum unsigned value must be larger than zero.

Signed Less Than

Signed numbers are more tricky than unsigned numbers. It is no longer sufficient

to just check of overflow. For instance, if you take 0x0001 and subtract

0xFFFF you get 0x0002 (1 - -1 = 2). This operation results in a carry, and

this makes sense if this were an unsigned operation, as 0xFFFF is much

larger. But looking at this as a signed operation, it is clear that no overflow

occurred, and that 0x0001 is not less than 0xFFFF.

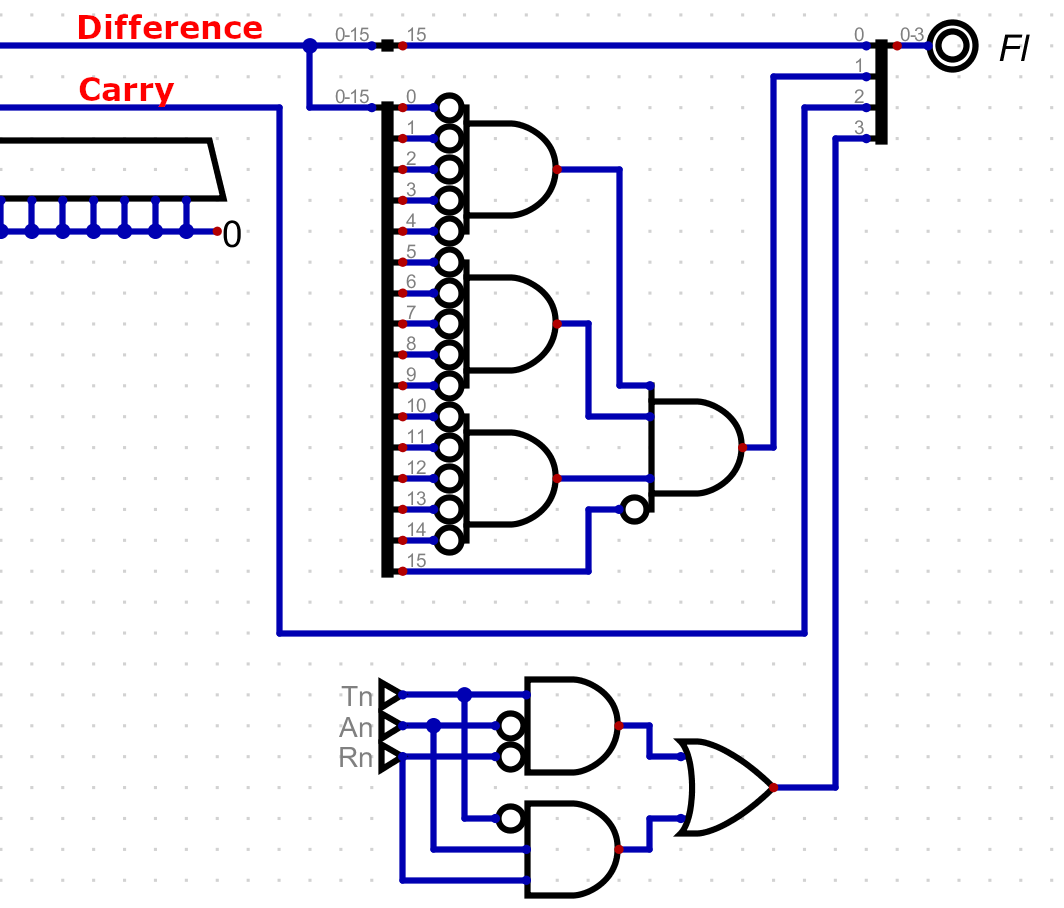

What I want to define is a signed overflow, which will have the same simple

property as carry does for unsigned numbers. It turns out that this has a fairly

simple equation: (Tn & ~An & ~Rn) | (~Tn & An & Rn), where Tn, An, and

Rn are whether or not the target, argument, and result are negative

respectively.

Flags

The comparisons that I have discussed so far will be the core of the flags. As a summary, this includes a zero flag, which will let me test for equality, a carry flag which is defined well for both addition and subtraction, and a signed overflow flag, which so far is only well defined for subtraction. I also will include a negative flag, which just if the signed interpretation of the number is negative. In other words, is the most significant bit a one. All of this is encoded into the ALU, as shown below.

The ALU has one four bit flag output, with each bit representing one of these flags. The next thing I need to to is save the flag output between instructions, which I will do with a register. This value needs to be saved because the comparison is part of a different instruction than the jump itself.

I will save the value of the flags in this register for any instruction that writes the ALU output to the data buffer. This might change later, but for now this essentially correlates to executing the comparison. This also means that other register operations will update the flags, not just the comparison operation.

The Jump Instruction

The jump instruction itself will move program execution to a new address. It will need two pieces of information: the type of jump, and where to jump to. The jump type can be on of the conditions described before, as well as jumps for other flag values. I also want a special value that will always jump.

I need to allocate the bits in the jump instruction. First, I will take the next

4 bit op code 0b0100. Next, I know of 13 types of jump that I want to be able

to perform, so I will reserve the next 4 bits of the instruction for the jump

type. This leaves me with three reserved typed, which may find use later. This

leaves me with 8 bits that I can use to define a location.

8 bits is not enough to describe a full 16 bit address. Instead, I will treat it

as a signed 8 bit number and encodes an offset from the next instruction. The

fact that it is relative to the next instruction is because the PC saves the

address of the next instruction, rather than the current one. If a jump happens,

then the offset will be added to the PC, rather than just going to the next

instruction. This leaves me with the following format: 0100JJJJOOOOOOOO.

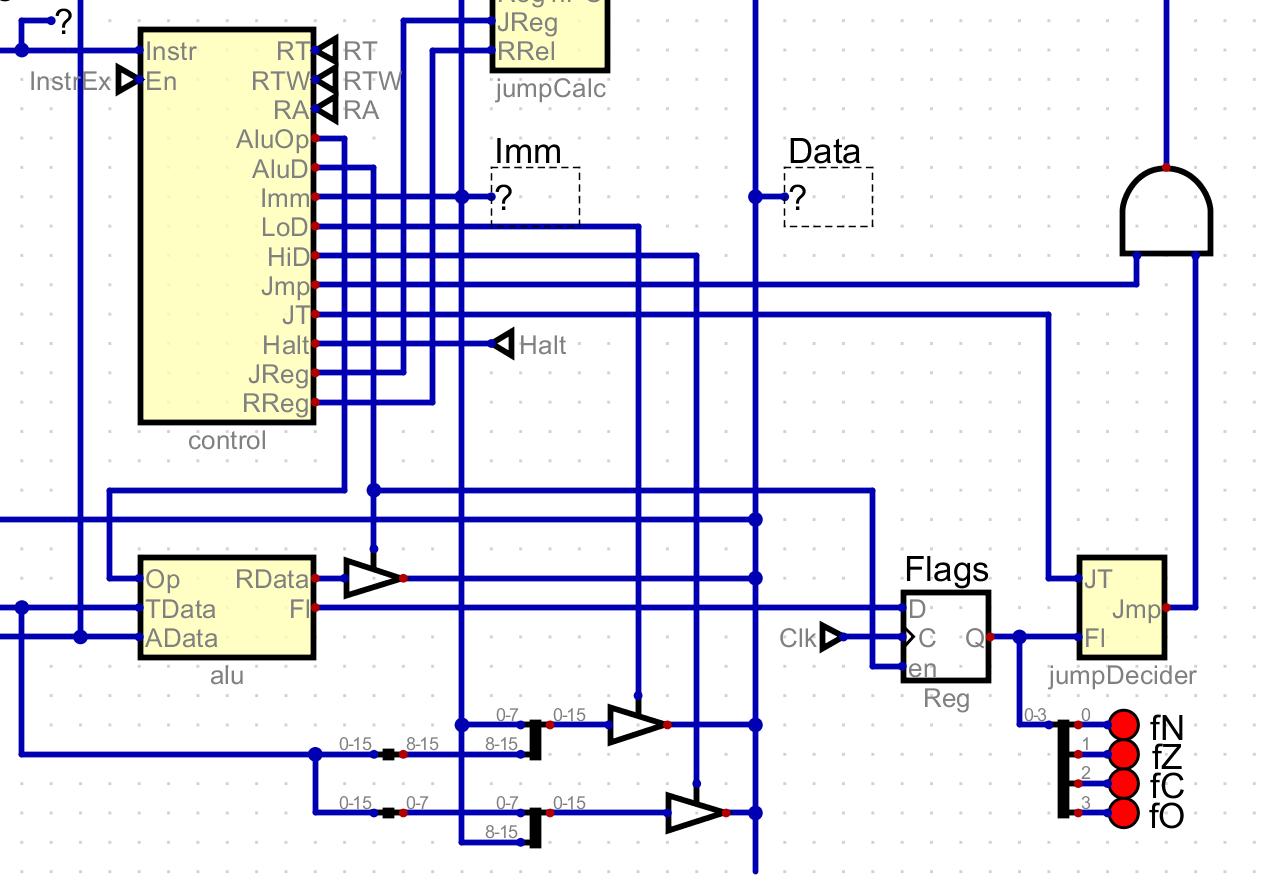

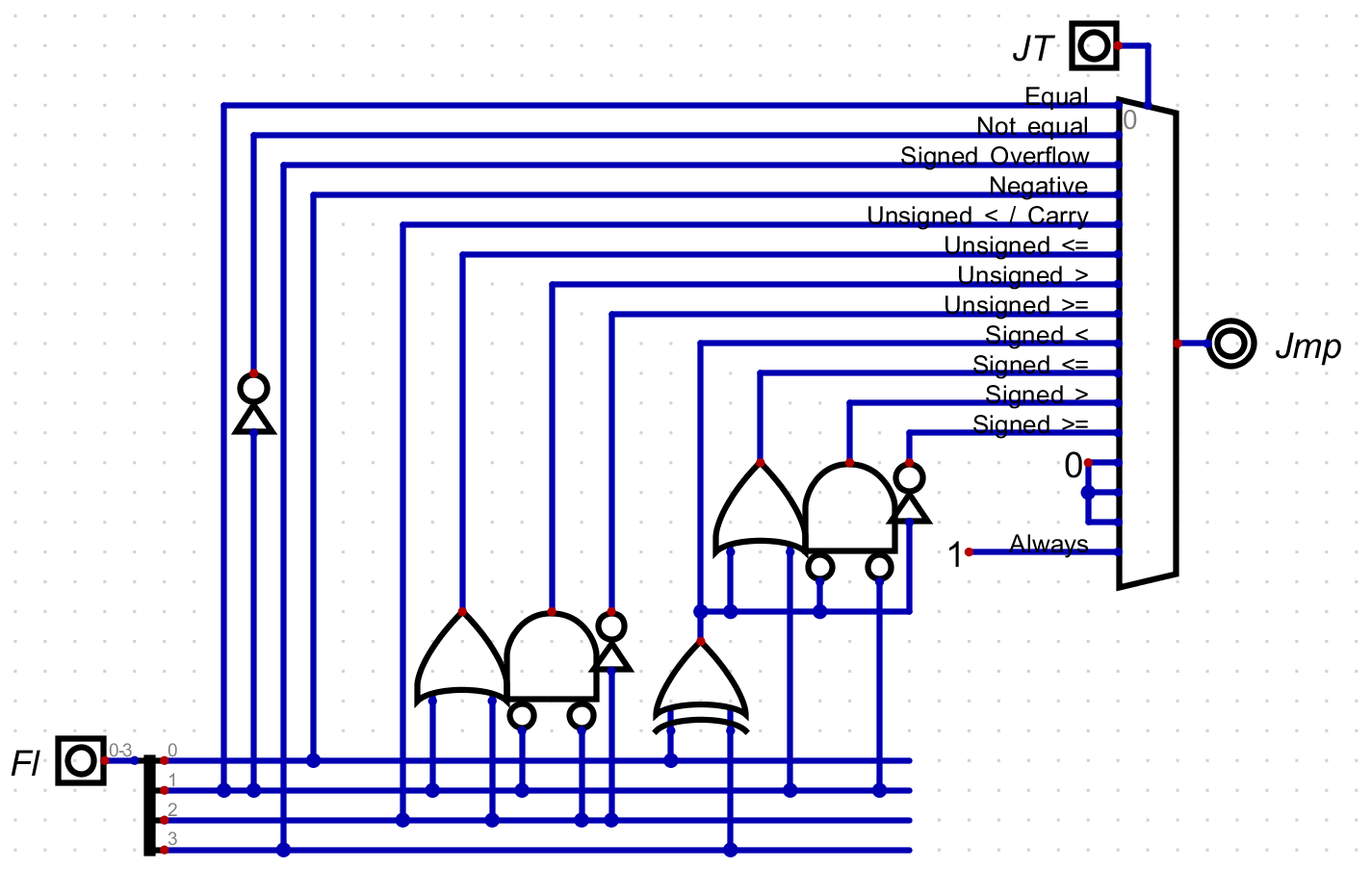

Deciding to Jump

Using the flags, I can determine if a jump should or should not be executed. You

may have noticed the jumpDecider module in the previous screenshot. It takes

the saved flags along with the jump type and determines if a jump should occur.

The first four are fairly simple, and just pass a flag or its inverse. The next eight types are unsigned and signed comparisons. You might notice that there are two similar structures there. These encode the logic I talked about earlier, where you can define the four comparison operations using just equals and less than.

As described, the difference is how less than is defined. As previously described, for an unsigned comparison I just use the carry value. This also means that I don’t need a separate type for jumping when a carry happened, this one type can do both! Later when creating a language, I could include both of these so that the code is clear, but they both use one instruction.

For signed comparisons, I use both the signed overflow and the negative flag. This is because if the argument was larger than the target you will get a negative value, unless you overflow in which case the result is inverted. Lets think about this with a few examples in four bits.

| Equaltion | Flags | Description |

|---|---|---|

3 - 5 = -2 | N | The result is negative without overflow, so you get that three is less than five |

-4 - -2 = -2 | N | The result is negative without overflow, so you get that negative four is less than negative two |

-1 - -3 = 2 | None | The result is not negative without overflow, so you get that negative one is not less than negative three |

6 - 2 = 4 | None | The result is not negative without overflow, so you get that six is not less than two |

5 - -5 = -6 | NO | The result is negative but with overflow, so you get that five is not less than negative five |

-8 - 1 = 7 | O | The result is not negative but with overflow, so you get that negative eight is less than one |

This XORed value is used as the less than value and is put through the same logic for less than or equal, greater than, and greater than or equal.

The three reserved types follow, never allowing a jump, and the final type always jumps.

Executing the Jump

Now I know if I want to jump or not, so the next step is to execute it. This

involves two pieces. First, only jump when the control module requests it.

Without this, the computer will jump randomly when the flags and type (which is

really just some bits from the instruction) happen to look like a valid jump.

This is achieved by ANDing the output of the jumpDecider with the Jmp

control line.

Second, add a module that adds the value of the PC with the jump offset. This is just a standard addition module, but I do have to extend the 8 bit offset to 16 bits, extending the sign bit. These two values are fed into the PC, with the combined jump signal enabling value storing, and sending the summed value as the value to store.

Halt

In addition to jump instructions, I added the HALT instruction. It is a generic

instruction, and is defined as 0x0000FFFFFFFFFFFF. It stops execution of the

computer, and is useful for knowing when your program is done.

Calculating Fibonacci

With this simple setup, I have the tools needed for control flow, which gives me

the tools needed to write a simple program that computed Fibonacci numbers.

Specifically, I would like to calculate the first Fibonacci number that is less

than or equal to a given value N.

; setup values for Fibonacci

; assume that register 0 already has 0

Load Low 0x1 into register 1

; load N

Load Low 0xFF into register 2

LOOP:

Add register 1 to register 0

; If register 0 is now larger than register 2, register 1 is the answer

Compare register 0 to register 2

Jump to :R1 if greater than

Add register 0 to register 1

; If register 1 is now larger than register 2, register 0 is the answer

Compare register 1 to register 2

Jump to :R0 if greater than

Jump to :LOOP

R1:

Move register 1 to register 3

Jump to :HALT

R0:

Move register 0 to register 3

HALT:

HaltThis program makes use of jump instructions ins various ways. One is a

conditional jump, like an if in higher level languages. You can see this

happening when a comparison is executed before a conditional jump. For this

program, I use it to check if the computed value is greater than N.

This program also needs a loop, continually executed until a value greater than

N is found. This is achieved by always jumping back to the start of the loop.

The only way out is through one of the if conditions.

I also use a jump towards the end, skipping over the instructions after :R0 if

the program jumped to :R1. This doesn’t have an exact parallel in higher level

languages, at least that I can think of. It is a detail about how I get the

right value into register three.

One thing you might notice is that I used labels, but that the jump instruction takes an offset. In order to convert this code into instructions, I will have to calculate the offset from the usage of the label to its position. As a first step, I will convert other instructions, remove comments, and add line numbers.

00 0x2101

01 0x22FF

02 LOOP: 0x1001

03 0x1302

04 0x46?? ; to :R1

05 0x1010

06 0x1312

07 0x46?? ; to :R0

08 0x4F?? ; to :LOOP

09 R1: 0x1231

10 0x4F?? ; to :HALT

11 R0: 0x1230

12 HALT: 0x0FFFTo fill in the offsets (?? above), take the line number of the destination,

and subtract the line number of the instruction after the source. This gives the

following program, which is included as prog.bin in the git repository.

0x2101 0x22FF 0x1001 0x1302 0x4604 0x1010 0x1312 0x4603

0x4FF9 0x1231 0x4F01 0x1230 0x0FFFRunning this will generate the largest Fibonacci number under 0x00FF, which is

0x00E9, and place it in register 3. This program won’t work for any number, as

the comparison take place after addition. This means the result could overflow,

resulting in a smaller number. I do have an instruction to check for a carry, so

I could take this into account, but I would rather move forwards with the

hardware.

Register Jump Instruction

While looking at jumping, I would like to add an instruction that uses a value in a register rather than the immediate value. This instruction will allow for both relative and absolute jumps, and this will solve for several gaps at once. This also provides a way to jump to any address by loading it into a register.

The jump instruction uses every bit, and I don’t want to take away a bit from

the immediate value. Because of this, I will use the next op code, 0b0101.

This jump instruction still takes a jump type, so the next four bits will be the

jump type. The register jump needs to know which register to look at, and for

that purpose I will use the least significant four bits. I want to use these

because they correspond to the argument in other operations, and it feels

natural: 0101JJJJXXXXAAAA.

This leaves four bits unused. I will use one of them, bit 4, to switch between

relative and absolute jumps. I don’t have a use for the other three bits yet,

but maybe I will find some later. This means the final instruction has the

following form: 0101JJJJXXXRAAAA.

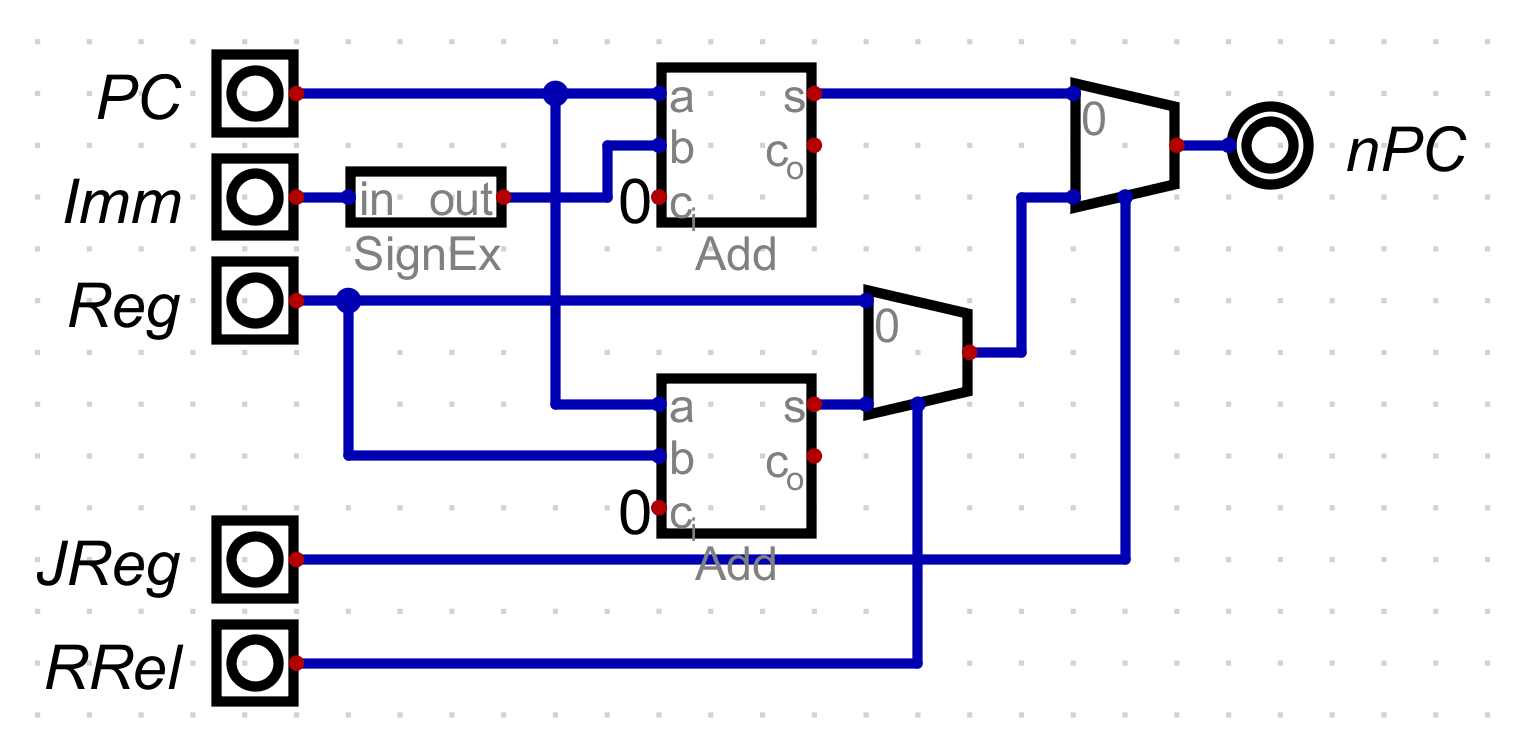

This instruction adds a few control lines that are fed into a new module, the

jumpCalc. This replaces the addition circuit that simply added the immediate

value to the PC.

This circuit take the PC, immediate, and the value of the current argument

register. It also takes two control signals, JReg and RRel. When JReg is

low, the immediate value plus PC is used. If it is high, then you have to look

at the value of RReg. If it is high, then add the value of the register to the

PC. If it is low, just jump to the value of the register. Taken together, this

circuit allows for both relative jumps with the immediate value and both

relative and absolute jumps with register values.

I wrote a simple test program called registerjump.bin. It sets up two values

in registers and then jumps back and forth between two register jump

instructions.

0x2004 0x2102 0x5F10 0x0FFF 0x0FFF 0x0FFF 0x0FFF 0x5F01This instruction will become even more useful as I add the ability to read and write from memory.